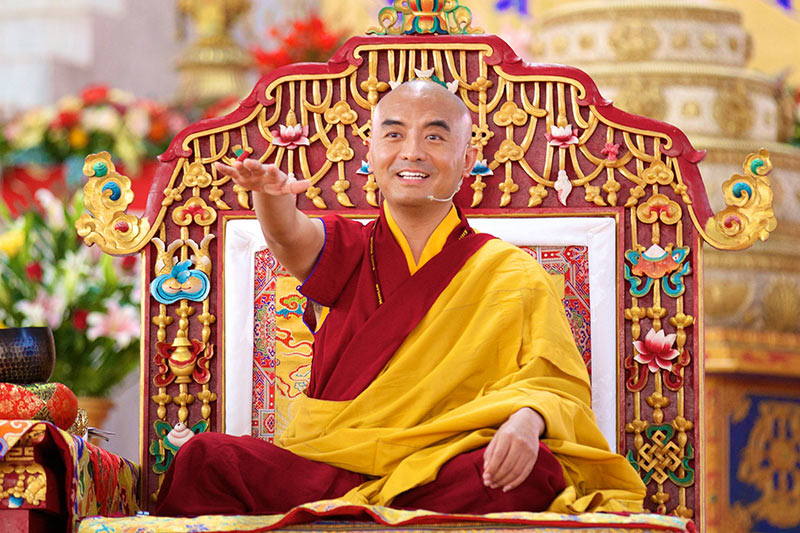

Mingyur Rinpoche’s final session of meditation instructions brought together the meditation experiences of the previous two days and, at the request of the 17th Karmapa, focused especially on mahāmudrā.

Rinpoche began by reminding everyone that the motivation of all Buddhist practice should be bodhichitta— to be able to bring ultimate benefit to sentient beings as limitless as space. They all possess the buddha nature but fail to recognize this because of ignorance, which is the result of karma. They wander in the three realms and six classes of saṃsāra and though suffering is but a dream, they create suffering, he said. We meditate and listen to the dharma in order to bring them to the state of buddhahood. Using this as the basis for the first meditation of the session, Mingyur Rinpoche instructed everyone to adopt the seven-point meditation posture and reflect on bodhichitta.

Next, Rinpoche led everyone in a śamatha meditation with the breath and body as a support. Close the eyes and focus on the breath, he instructed. After a minute or so, he began a meditation on the foundation of body and feelings. Beginning at the crown of the head note the sensations. Move the attention to the nape of the neck, to the back and so forth. Repeat this until you have scanned the whole body. Now direct your attention to any general sensation you feel across your body such as heat or tiredness, sleepiness, discomfort, unhappiness or pain. “If you are viewing them,” he reminded us, “you will not be controlled by them. If you are looking at the river, you will not be carried away by it.”

Mingyur Rinpoche then summarized the main points of mahāmudrā that he and Gyaltsap Rinpoche had covered. In general, he explained, there are three types: sutra, tantra and essence mahāmudrā.

Mahāmudrā means primarily a stamp or royal seal. This means that there are no phenomena that go beyond the expanse of mahāmudrā: the nature of mahāmudrā contains all phenomena of saṃsāra and nirvāṇa. Sutra mahāmudrā is primarily taught in texts such as the King of Samadhi Sutra. These are the words of the Buddha. In the commentaries, it is taught primarily in the Uttaratantra [Maitreya’s Sublime Continuum]. Tantra mahāmudrā is practised primarily in the Six Yogas of Naropa and uses tantric methods working with the winds, channels and drops. It focuses on the creation and completion stages, examining the emptiness of great bliss and the meaning of the co-emergent wisdom. Essence mahāmudrā is primarily when the guru points out the nature of mind with pith instructions and you recognize it, based primarily on devotion to the guru and bodhichitta.

The aim of all mahāmudrā is recognition of the buddha nature which is found in all sentient beings, Mingyur Rinpoche explained. It is present within all of us: everything we think and do occurs within the expanse of the buddha nature. It doesn’t become worse in saṃsāra or better in nirvāṇa because it is the basis of both If we recognize our own nature, we will gradually achieve buddhahood.

The Aspiration of Mahāmudrā reads: By not realizing this, we wander in saṃsāra.

‘This’, Rinpoche commented, refers to the ordinary mind which is aware, experiences and thinks. The essence of this ordinary mind is the buddha nature. If we recognise this, we become buddhas otherwise we wander endlessly in saṃsāra.

In mahāmudrā we employ three stages of meditation in order to recognise this: shamatha meditation, insight meditation, and the union of shamatha and insight. In mahāmudrā shamatha is called ‘searching for the view through meditation’. First, we use shamatha to establish meditative concentration, and then we recognize the essence and establish the view. In mahāmudrā insight meditation, we receive pith instructions on searching for the mind from the guru, then we investigate thoroughly, thus we come to the view, and, finally learn to rest in the view without distraction. We can also go between the two using them in union.

Mingyur Rinpoche elaborated that because there were practice requirements for pointing out instructions, so he was not allowed to give those to a general audience. However, the meditations he had used over the previous two days were the first stage of shamatha meditation and suitable for everyone. They were imbued with the flavour of mahāmudrā and followed Jetsun Milarepa’s three points: don’t wander; don’t meditate; don’t fabricate.

There are three important meditation instructions, Rinpoche continued: stillness, motion and awareness. Stillness is mind resting in its own nature; motion is the mind thinking about different things; awareness means just knowing. If we are still and we know it, if our mind is in motion and we know it, we are in meditation. But just as important as meditation, we need to develop the qualities of compassion, devotion to the guru, and dedication. These combined will eventually lead us to recognise the nature of the mind.

Mingyur Rinpoche then led two meditations, the first on stillness, followed by one on the mind in motion.

Meditation on stillness (shamatha without the attributes):

a. Let the mind relax as it is, like when you take a deep breath. Even if you know how to meditate, you shouldn’t. Breathe in slowly, hold your breath, let it out through the mouth forcefully, and then relax. That feeling of relaxation is awareness. You are aware of being relaxed.

b. The instruction is “Don’t wander; don’t meditate”

Just rest the mind, without it being distracted. You are aware.

After scanning the body, just rest in open awareness, in equipoise, letting thoughts come and go.

Meditation on the mind in motion (how to meditate one-pointedly on thoughts):

Don’t block thoughts, let them become the support for the meditation. Yesterday the breath was the support for the mind to be undistracted. Similarly we watch the thoughts as they come and go. We think about many different things. When we meditate on thoughts we need to watch the thoughts, like the thumb counting beads on a mala. Our awareness is watching the thoughts.

In place of the breath, in place of sound, watch your thoughts without being distracted.

Now let your mind be.

Meditation on thoughts usually has two outcomes, Rinpoche observed:

1. The thoughts disappear when you watch them; usually when we meditate there are too many thoughts but when we try to watch them they disappear. Why? Because the mind has come into stillness. No longer distracted for an instant or two. Rest in that instant. The watcher is awareness.

2. You can watch the thoughts one after the other, like watching TV. The thoughts come here, go there.Only a few people are able to do this, because most people get distracted by their thoughts.When you are watching your thoughts you are not being controlled by them.

When you can see the river, you are not in it.

Whichever outcome, he reassured people, was excellent.

The greatest obstacle to the quality of meditation, he warned, is distraction. Torpor, dullness, agitation can all be used as a support to meditation, but if we forget to watch that’s insurmountable. Non-distraction is the essence of meditation. People sometimes focus mistakenly on bliss or non-thought, but these are experiences not the essence of meditation. As the Short Vajradhara Lineage Prayer instructs:

The main practice is being undistracted, as is taught.

As ones who, whatever arises, rest simply,

Not altering, in just that fresh essence of thought…

Whatever thoughts arise, we should not try to alter them or stop them, he advised. Even if the thoughts are inappropriate, rude, and superstitious and so on, we should not try to alter them; the practice is to rest in the essence uncontrived without distraction.

Non-distraction is awareness. Whether we are resting in stillness in shamatha or resting in motion, both are resting in awareness. Since we were born, we have had a string of thoughts but they weren’t meditation, he added wryly. Only when awareness is present does it become meditation.

Mingyur Rinpoche then provided some pointers for the stages ahead in mahāmudrā meditation. This practice of stillness, motion and awareness within mahāmudrā is part of shamatha, he explained. If we begin with bodhichitta and devotion to the guru, if we supplicate the guru, and then engage in this practice of stillness, motion and awareness in mahāmudrā, the awareness will dissolve into the stillness and the motion. At that point the three will become two.

As we continue to meditate, those two —the awareness-in-stillness and the awareness-in-motion—become one, like waves subsiding into the water. Everything becomes a display of awareness. At this point there is no object of meditation and no meditator; nothing apprehended no apprehender; no doing, nothing done; no subject, and no object. Everything coalesces into one.

Some people are concerned at this point that something is amiss with their meditation. In fact, this is recognising the nature of the mind, and the stage known as ‘arriving at the level of lesser simplicity’.

If you persevere and continue to put effort into practice, you will definitely achieve realisation, he assured everyone.

Mingyur Rinpoche then spoke of the Three Stages of Awareness. Usually our awareness is mixed up with the afflictive emotions.

A. Through mahāmudrā practice we recognize awareness and that becomes the main aspect of our meditation. There are various methods and supports we can use for our meditation to strengthen our awareness. The object is irrelevant. This awareness, however, still has an aspect of subject/object, an elaborate conceptual aspect, it’s like ‘the sky and the earth’.

B. The second stage of awareness is called the ‘herdsman’s awareness’— the tending awareness.

C. At the point where we have recognized the nature of the mind, the mind becomes self-aware; aware of its own nature – the union of clarity and emptiness. We can experience this through the state of meditation. It cannot be taught in public. There are pith instructions through which we can experience the mind free of elaboration: it becomes clear, brilliant, vivid and direct. Yet at the same time there is nothing to be found. This is buddha nature. It is there the whole time but we do not see it. It is hidden in plain sight.

Mingyur Rinpoche concluded the third session with a short guru yoga meditation and instructions on how to make dedications. Resting in the nature of emptiness is the best way, he commented, but, alternatively, you can imagine that all the buddhas and bodhisattvas are in front of you as you make the dedications for the benefit of all sentient beings.

The meditation session had begun with generating bodhichitta and the resolve to bring all sentient beings to the state of buddhahood. Now it concluded with the dedication of any merit gained that all sentient beings might attain buddhahood and that the Gyalwang Karmapa might have a long life.

Although Mingyur Rinpoche had been unable to give direct pith instructions to a general audience, he had used those three afternoons through skillful means to bring the essence of meditation into everyone’s experience. And, as people drifted away to their own rooms, they spoke of how extraordinary the sessions had been and how blessed.

In the first session of his pre-Monlam teachings, Mingyur Rinpoche distilled the essence of meditation, practicing non-distracted awareness. He began the afternoon by summarizing the profound teachings on mahāmudrā detailed in Goshir Gyaltsap Rinpoche’s commentary on the Aspiration of Māhamudrā of Definitive Meaning. Mingyur Rinpoche said these pith instructions are a distillation of the Buddha’s 84,000 teachings. To make it even easier for us, Mingyur Rinpoche joked, he had kindly condensed these 84,000 teachings into three key points: preparation, main practice, and follow through.

In the first session of his pre-Monlam teachings, Mingyur Rinpoche distilled the essence of meditation, practicing non-distracted awareness. He began the afternoon by summarizing the profound teachings on mahāmudrā detailed in Goshir Gyaltsap Rinpoche’s commentary on the Aspiration of Māhamudrā of Definitive Meaning. Mingyur Rinpoche said these pith instructions are a distillation of the Buddha’s 84,000 teachings. To make it even easier for us, Mingyur Rinpoche joked, he had kindly condensed these 84,000 teachings into three key points: preparation, main practice, and follow through.